Explore the Canal Walk in Downtown Richmond

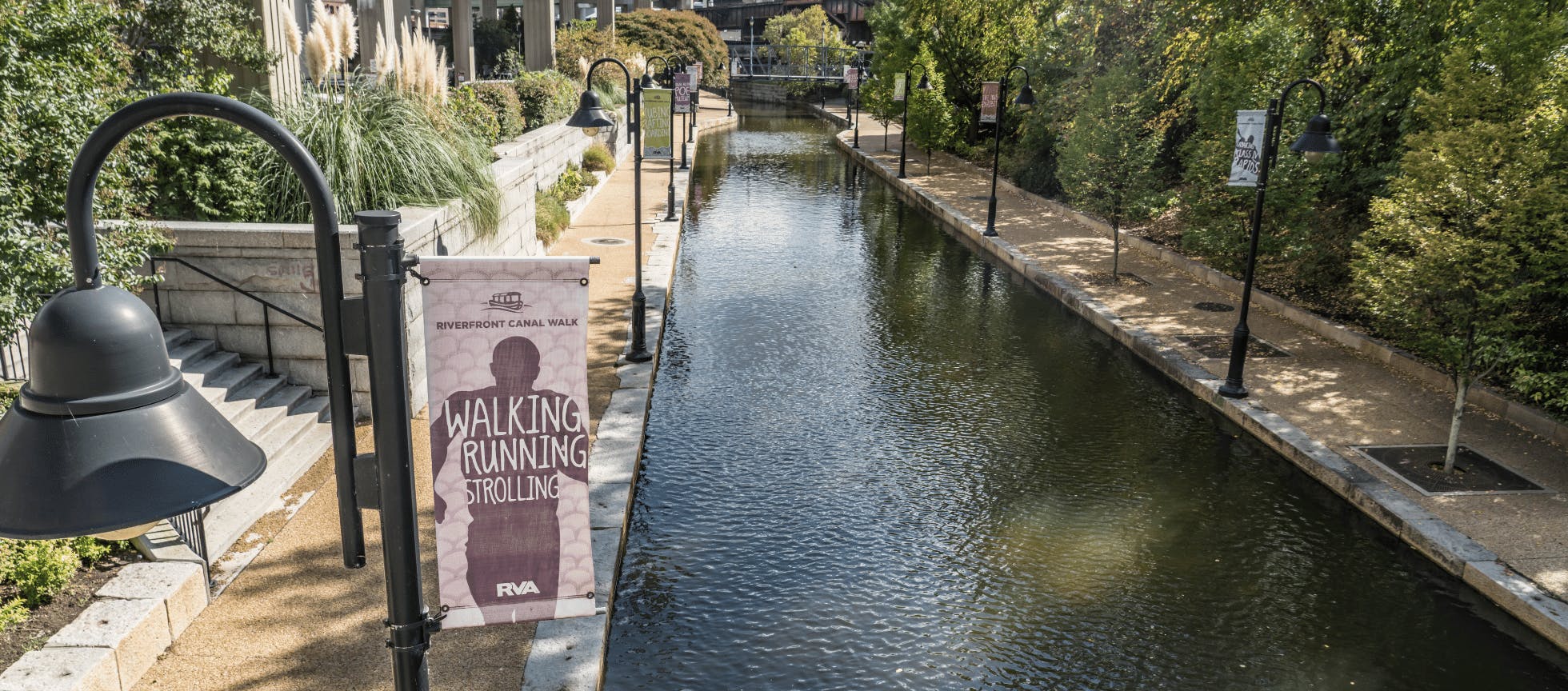

Enjoy a walk, bike ride or a Riverfront Canal Cruise along the historic Canal Walk!

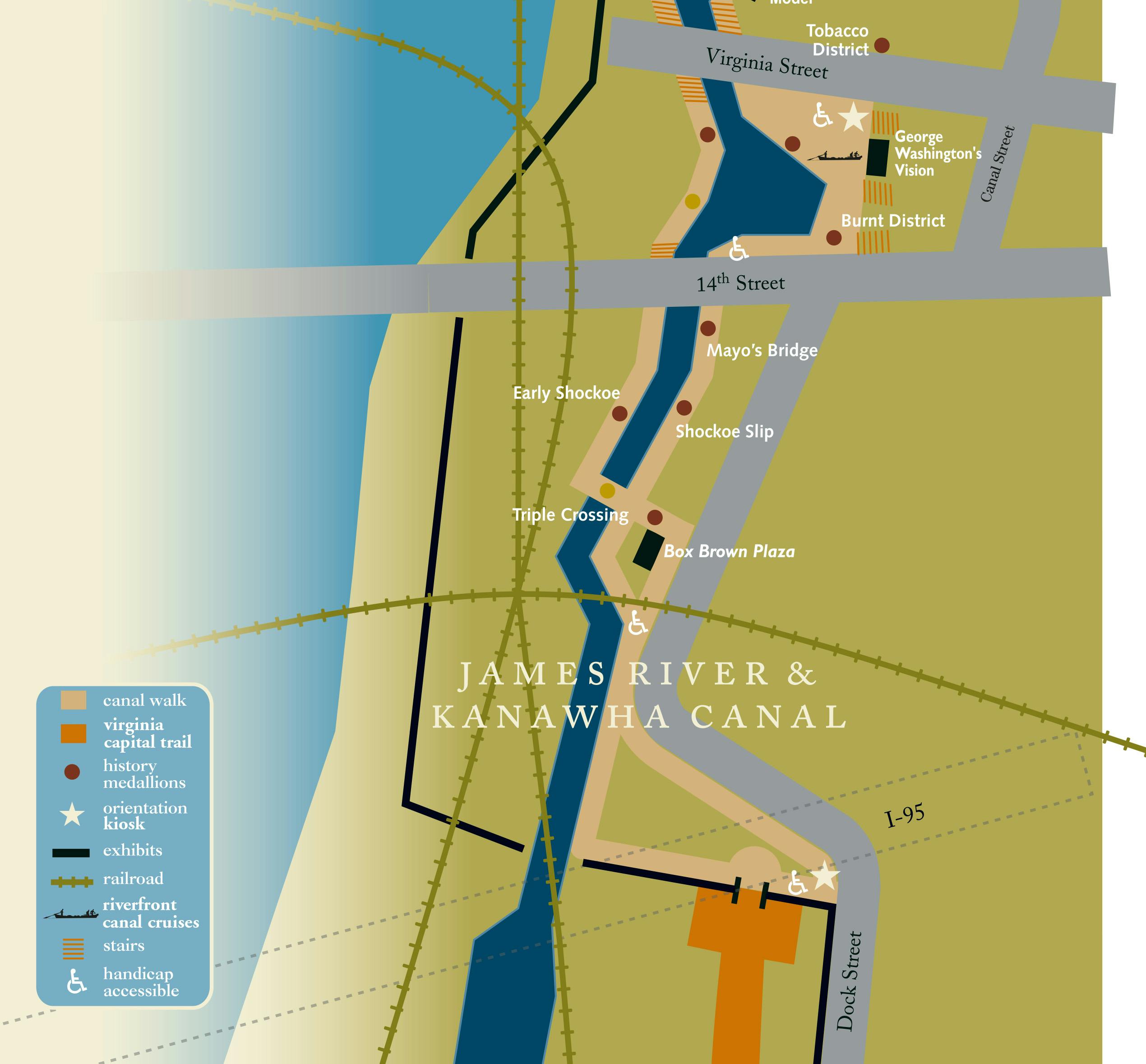

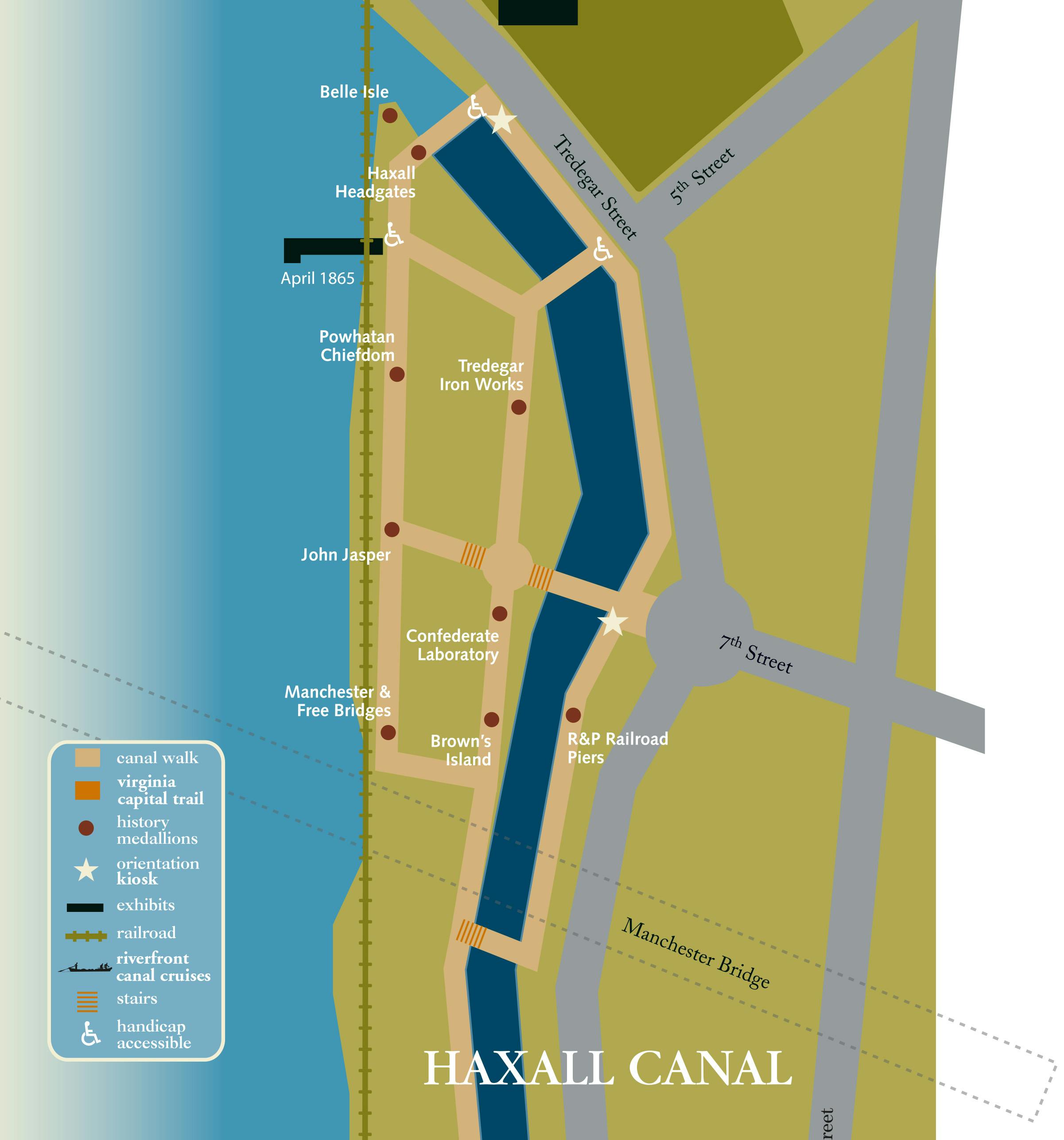

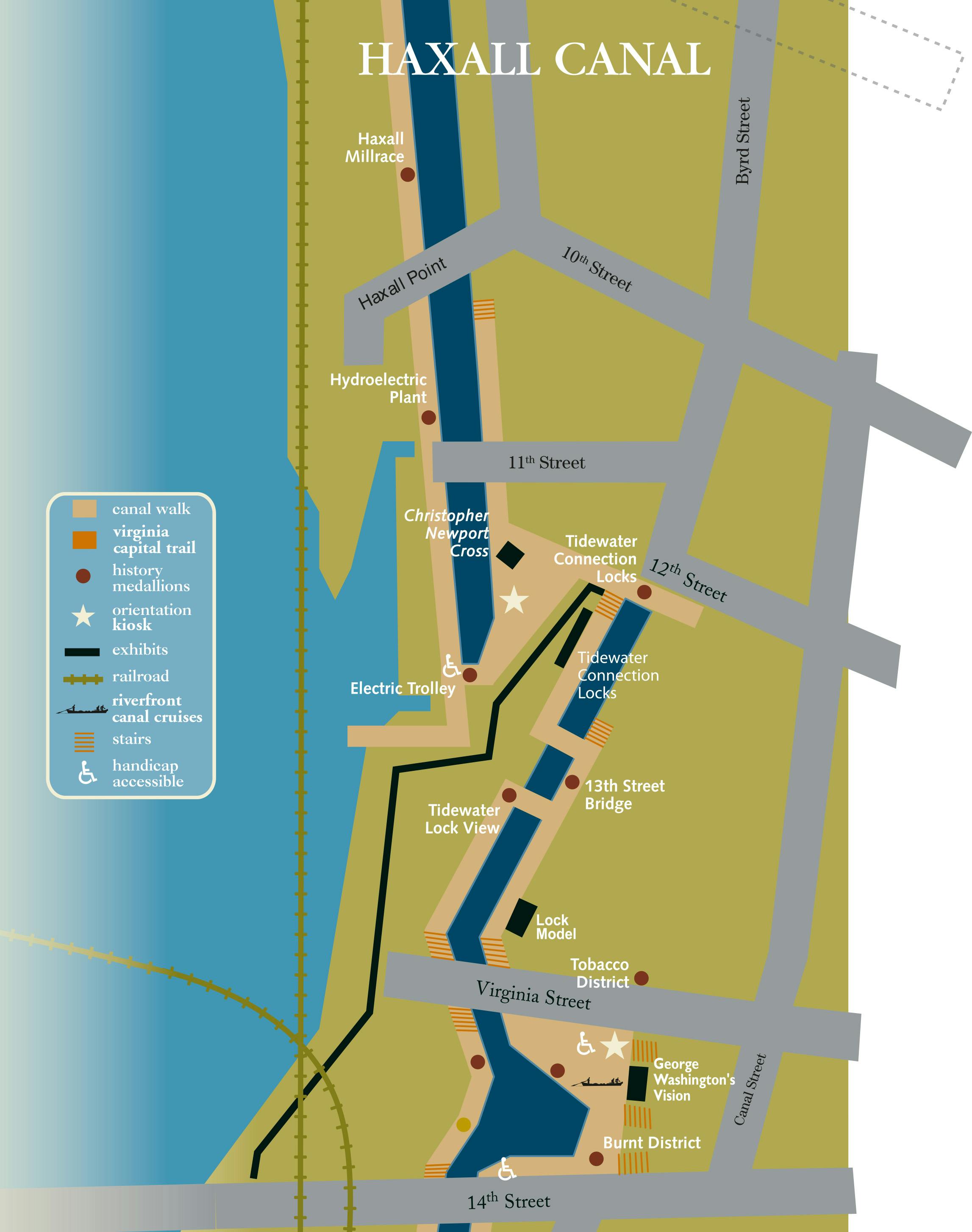

The Canal Walk has been a staple of Richmond for decades, entertaining visitors and residents alike. Located along downtown’s riverfront, the Canal Walk stretches 1.25 miles along the James River and Kanawha and Haxall Canals, and has access points at nearly every block between 5th and 17th Streets.

The Canal Walk is used for walking and biking by visitors, residents and people enjoying a break from working downtown. Did you know that you can explore the canal by boat, too? Find out more about Riverfront Canal Cruises.

There is so much to learn about Richmond’s history along the Canal Walk. On your walk you’ll see public art, statues and exhibits. Learn all about the Riverfront Art here.

Visit exceptional restaurants along the Canal Walk, like Southern Railway Taphouse, Casa del Barco and Bottom's Up Pizza.

How Can I Access the Canal Walk?

The Canal Walk in Richmond has access points at nearly every block between 5th and 17th Streets.

There are handicapped-accessible entrances at 5th, 10th, 12th, 14th and 16th Streets.

Canal Walk Parking and Transportation

- 1200 E Byrd Street (Reynolds lot), Public parking 24/7, See signage and pay-to-park kiosk on-site

- 8th & Cary Parking Deck, See signage and pay-to-park kiosk on-site

- See MAP for additional parking options

- Bike racks are located along Low Line Green, the Turning Basin, next to Casa Del Barco, on Tredegar Street near 5th Street and the vehicular bridge on the western end of Brown’s Island (nearest historic Tredegar).

- Find more information about Parking and Transportation in Downtown Richmond here.

The History of the Canal

Richmond, lying on the fall line of the James River, was destined for a history steeped in canal navigation. George Washington, a staunch proponent of canal transportation, appeared before the Virginia General Assembly in 1784 to support legislation to create a waterway to bypass the falls. By linking the James River with the Kanawha River in western Virginia, which in turn flowed into Ohio, he hoped to improve transportation and trade with the western region. In 1785, the state incorporated the James River Company, with Washington as the honorary president. The James River Company set to work constructing the first towpath canal system in North America. The first section of the canal system to be completed circumvented the seven-mile falls near Richmond.

By 1800, the Great Basin was situated in the heart of the city. Partially located under the present-day James Center, the basin was a hub of activity surrounded by mills and warehouses. The Tidewater Connection was completed in 1822, and boats could enter the canal below the falls. Wooden locks and the Richmond Dock connected the lower James to the Great Basin via canal to the upper James. The locks, however, would soon decay and be replaced.

In 1820, the James River Company signed their charter over to the state, which controlled the company until 1835, when the James River and Kanawha Company took over the canal effort.

Richmond's Canal: Then and Now

By 1840, canal construction was completed from Richmond to Lynchburg and by 1851 had reached what would be its final destination — Buchanan in Botetourt County. At this point, the canal system spanned 197 miles. Finally, 1854 brought improvements to the Tidewater Connection: five granite locks (the fourth and fifth still exist near the intersection of 12th and Byrd Streets) and turning basins between 9th and 14th Streets; the Richmond Docks, located between 14th and Pear Streets; and the Great Ship Lock near Dock and Pear Streets.

These improvements ushered in the heyday of the James River and Kanawha Canal in Richmond. During the 1850s — and peaking in 1860 — canal traffic was at its busiest. As many as 195 boats regularly traversed the waters, bringing goods such as tobacco and wheat from western Virginia to market, and returning home with finished goods from the city.

Passenger voyages made up a small percentage of boat traffic. Only six passenger boats — called packets — ran on a regular basis during this busy time. Packets could carry 30 to 40 people and took approximately 33 hours to reach Lynchburg via canal. From the packet office in the Great Basin, the boats were poled out to 7th Street where they were hitched up to a horse or mule. The animals pulled the boats along the towpath while a boatman steered from the rear. On nice days, passengers sat on the deck of the boat and enjoyed the leisurely journey.

All this came to an end as flooding, Civil War damage and competition from the expanding railroads took a huge toll on the Richmond canals. By 1880, the Richmond and Allegheny Railroad was laying tracks along the towpath of the canal. Canal construction never reached the Kanawha River as George Washington envisioned.

In the late 20th century, the canals were reconstructed as part of a broad vision for downtown Richmond’s riverfront. Design and construction phases lasted from 1991-1999, with the groundbreaking ceremony on October 5, 1995. June 4, 1999 was the grand opening ceremony for the Canal Walk and canal boat christening. Riverfront Canal Cruise public tours started the next day. This existing canal system was constructed in conjunction with the Department of Public Utilities Combined Sewer Overflow project. A pipe measuring 1.3 miles long and up to eight feet in diameter was installed in the bed of the Haxall and Kanawha canals from west of the Lee Bridge eastward to 16th Street. The pipeline collects wastewater and, when the city sewers are overwhelmed, routes it to a 50-million gallon Shockoe retention basin until it can be treated at the wastewater treatment plant.

History Medallions on the Canal Walk

Find over 20 history medallions along downtown Richmond's Canal Walk!

22 bronze medallions can be seen along the Canal Walk embedded in the path as markers of the following historic sites. On the maps below, you will see each medallion marked as a red dot. Find them along your walk and learn about Downtown Richmond history as you go!

Haxall Headgates

The Haxall Canal was originally a millrace, dug by David Ross in 1789 to power his flour mill. When the mill was acquired by the Haxall family in 1809, the race became known as the Haxall Canal. It was eventually extended from 12th Street all the way to the Tredegar Iron Works.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, prisoners poured into Richmond Camps built originally as transport stations for prisons farther south. At times, the camp on Belle Isle held up to 8,000 Union men. Over the course of the war, several thousand prisoners died, many during the harsh winter of 1863-1864 when the entire city was overcrowded and undersupplied. Plan your visit to Belle Isle here.

Powhatan Chiefdom

Native Americans lived along the James River as far back as 10,000 B.C. By the 17th century, when the first European explorers arrived at the falls of the James River, the Powhatan had established a chiefdom that extended from the falls all the way to the coast, a territory called "Tsenacommacah."

Tredegar Iron Works

The Tredegar Iron Works, along with the Armory that once stood beside it, was the greatest industrial complex in the Civil War-era South. Run by Joseph Reid Anderson, the Iron Works, with a force of immigrants and free and enslaved blacks, produced up to half of all of the armaments used in the Confederate war effort.

John Jasper

Born in a slave cabin, John Jasper became one of the most famous preachers of his time. Freed by emancipation in 1865 at the age of 53, he founded the Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church in one of the buildings that had housed the Confederate Laboratory on Brown's Island. In 1870, the congregation moved to Duval Street,where it remains today.

Confederate Laboratory

During the Civil War, the hazardous work of loading powder was carried out on Brown's Island because of its separation from the city by water. On March 13, 1864, a huge explosion in the laboratory killed 46 workers - mostly women whom hard times had forced into this dangerous occupation.

R&P Railroad Piers

From many spots on Brown's Island, the remains of the Richmond and Petersburg railroad bridge are visible. This was the railroad that brought Jefferson Davis to the city to be inaugurated as the President of the Confederacy in 1861. When the city fell to the Union army four years later, all of the James River bridges, including the R&P, were burned.

Brown's Island was created when the Haxall Canal was extended west to the Tredegar Iron Works. Encircled by waterways that provided power and transportation to flour mills, foundries and paper companies, Brown's Island has been at the center of Richmond's industrial activities for more than 200 years. The CSX Railroad still runs along its Southern edge. Plan your visit to Brown's Island here.

Manchester and Free Bridges

For years, the only river crossing for vehicles and pedestrians was Mayo's toll bridge, at 14th Street. Complaints about the tolls eventually led to the opening of Richmond's first “free” bridge in 1873. The day after it opened, thousands crowded onto the Free Bridge to watch the Reverend John Jasper conduct a large group-baptism ceremony in the river. The bridge was replaced in 1972 by the Manchester Bridge, which includes a legally mandated free walkway.

Haxall Millrace

From Colonial times, the waterpower of the James was used to grind wheat into flour. This became even more effective when millraces, like the waterway that ultimately became the Haxall Canal, were dug to divert water from the river for this purpose. In the 19th century, when the city became one of the largest flour exporters in the world, fleets of schooners and brigs carried Richmond's flour to Brazil and around Cape Horn to San Francisco and Australia.

Hydroelectric Plant

Power plants have stood along the Haxall Canal for more than 100 years. In 1901, the success of the city's electric streetcar system, which connected its downtown and growing residential areas, led the Virginia Railway and Electric Company to build a new hydroelectric plant along the Haxall Canal. The dramatic building still stands today.

Electric Trolley

In 1888, Richmond built the first commercially successful electric streetcar system in the world. The tops of the new cars were connected to an electrical line called a “troller,” and thus became known as “trolleys.” The streetcars ran for 60 years before giving way to buses and cars.

Tidewater Connection Locks and Tidewater Lock View

Canals and the locks that raised boats from one water level to the next were considered among the greatest engineering feats of their time. Only two of Richmond's canal locks remain. Preserved by the Reynolds Metal Company, these locks connected the Great Basin, between 8th and 11th Streets, with the Richmond dock at 14th Street. The locks are visible from two spots along the Canal Walk.

13th Street Bridge

The old 13th Street bridge was built by Richard B. Haxall and Lewis D. Crenshaw, proprietors of the Haxall-Crenshaw Mill, which once stood along the canal. In the vicinity of the bridge is an arch remaining from a lateral canal that extended into an auxiliary building of the flour mill. One of the largest mills in America, the Haxall-Crenshaw was surpassed only by the Gallego Mill, located a few blocks away.

Tobacco District

From Colonial times through World War II, Richmond was a center for tobacco inspection and processing. By the mid-19th century, the city had become the largest tobacco producer in the world, with more than 50 factories, including chewing tobacco and cigar manufacturers, box makers and label printers. Many tobacco warehouses dating from the late 19th and early 20th century still stand.

Burnt District

As the Confederates evacuated Richmond in 1865, they deliberately torched bridges, warehouses and arsenals to keep them from the Union army. More than 1,000 buildings burned between 4th and 15th streets, from Main Street to the river. All the buildings in the Shockoe Warehouse district were destroyed. The devastation was so complete, residents afterward had trouble identifying their own streets.

James River and Kanawha Canal

In its peak years, the James River and Kanawha Canal employed 75 deck boats, 66 open boats, 54 batteaux, 6 passenger boats, 425 horses and 900 men. The passenger boats, called "packets," ran between Richmond and Lynchburg. At night, the lower deck was divided into two sleeping compartments, one for men and one for women - but some passengers chose to remain above and contemplate the stars.

New Turning Basin

Due to Richmond’s canals being so narrow, “turning basins” had to be specially constructed so that the long barges and passenger boats could turn around. Richmond's original Great Basin stood between 8th, 11th, Cary and Canal Streets, and was connected by a series of locks to the Richmond dock. In 1999, a new turning basin for the restored canal was constructed between Virginia and 14th Streets. This new location is currently where Riverfront Canal Cruises start boat tours.

Mayo's Bridge

Bridges and ferry launches have stood at 14th Street since Richmond's earliest days. The city's first bridge across the James River, a toll bridge named after its owner, John Mayo, was completed in 1788. In 1865, Mayo's bridge was burned by the Confederate army as it evacuated the city.

Early Shockoe

Shockoe is Richmond's oldest neighborhood. In the late 17th century, tobacco, furs, rum and enslaved Africans were traded in the Shockoe area. In 1742, the town was no more than a fifth of a mile square, with 250 merchants, laborers, fishermen and boatsmen.

Built at the crossroads of Native trade routes, Richmond has always been a place where people, languages and goods have mingled. In 19th Century Shockoe Slip, Richmond's original Great Basin stood between 8th and 11th, and Cary and Canal Streets, and was connected by a series of locks to the Richmond dock, making the neighborhood a center for commerce and shipping.

Triple Crossing

Soon after the Civil War, railroad tracks were laid over the old canal towpaths. When additional lines were built in the early 20th century, Richmond became the only city in the world with a triple main-line railroad crossing, a dramatic intersection that can still be seen in operation along the James River and Kanawha Canal.